The Strategy of the Detour: Drama Therapy with Nicolas Bézier

From fairy tales to slow movement to group improvisation, Nicolas Bézier shows how drama therapy can unlock confidence, connection, and unexpected moments of healing.

Drama therapist, director, and visual artist Nicolas Bézier (nicolasbezier.art) speaks about his journey from painting and comics to discovering the healing power of drama. Based in Toronto, trained in Paris at INECAT, and inspired by everything from Butoh (a form of slow, expressive Japanese dance-theatre) to storytelling to intergenerational play, Nicolas uses movement, metaphor, and improvisation to unlock creative expression in people of all ages. In this conversation, he reflects on his artistic evolution, the power of group work, and why true healing never begins with a performance.

How did your artistic journey begin?

My first medium was drawing and painting. I was very passionate about it as a teenager, and I studied visual arts at the University of Bordeaux. But the approach there was very rigid. It felt almost like the army. They didn’t say it, but the message was: you have to forget everything and start over, do it the way we tell you. Before that, I had studied in Bayonne at an art school after my regular school, and there I had a teacher who encouraged me to explore my creativity and identity. So arriving in Bordeaux was a shock. It made me feel like the worst artist ever. It blocked me. I lost confidence, and slowly I quit. I stopped drawing or painting altogether and went into something else—administration, insurance. Nothing related to the arts. I left that part of myself for a long time. But eventually, I was miserable. I realized I would rather do something less stable that I loved than stay in that state. And that’s when I moved to Canada in 2006 and discovered acting.

Nicolas Bézier, drama therapist and visual artist. www.nicolasbezier.art

What drew you to acting?

I started with classes and then joined a group. It helped me so much. I had always been shy and introverted, and theater gave me a way to express myself and discover new sides of who I was. I also felt a strong sense of connection with others—it’s like finding a new family. That’s what led me to art therapy.

What stood out to you during your drama therapy training?

At INECAT in Paris, I discovered tools that became very meaningful to me—especially tales and movement. Tales are very therapeutic. You can always find a parallel with your own life. The main character has to go through challenges to reach a goal. They meet new people, face obstacles, and in the end, the treasure they find is already inside of them. The story mirrors a personal journey of growth. It helps people reflect on their own lives without doing it directly.

Movement was another big discovery. I had a four-day workshop with Alvaro Morell, and it helped me reconnect with my body: through very slow movements, I discovered sensations and emotions that I had never really paid attention to.

I call it a kind of poetry of the body.

That’s why I now always incorporate movement in my workshops, even if I don’t work only with drama. It’s another language.

How do you create a safe environment for people to open up in group sessions?

I always start with a ritual—a short meditation or active warm-up, so people can release tension and enter a creative space. Then I introduce symbolic exercises. For example, I’ll ask participants to describe how they feel today by imagining themselves as an animal or a landscape. That’s what we call la stratégie du détour at INECAT—the strategy of the detour. Instead of facing trauma head-on, we work through metaphor and imagination. We might work on relationships, discover new talents, or reconnect with the body—all without pushing into difficult territory too fast. Some people aren’t ready, and that’s okay. We focus on creative expression, not emotional confrontation.

And how does the group dynamic come into play?

Group work is very important. Movement helps a lot here. I’ll often start with exercises in pairs, like balancing a bamboo stick between just two fingertips while looking into each other’s eyes. It teaches presence, trust, and silent communication. I also use icebreaker games, like the group counting game. The group has to count from one to ten, but nobody knows who will say the next number. If two people speak at once, you go back to one. It sounds easy, but it creates a lot of fun—and teaches active listening and intuition. I’ve seen people come in feeling down, and after this game, they’re laughing. That’s powerful.

How do you adapt your approach across such a wide range of groups?

I always tailor what I do. With seniors, I adapt the movement so they can stay seated. I also work more with memory and cognition, like associative word games to stimulate the brain. Teenagers often don’t like meditation at first, so I offer more active warm-ups. They need to move. And when I worked with people with intellectual disabilities, like Down syndrome, I used props—hats, puppets, simple costumes—to help them separate from the character and feel more comfortable performing. Puppets are great for people with social anxiety because the focus is on the object, not themselves. It’s a nice trick: it removes pressure from their shoulders.

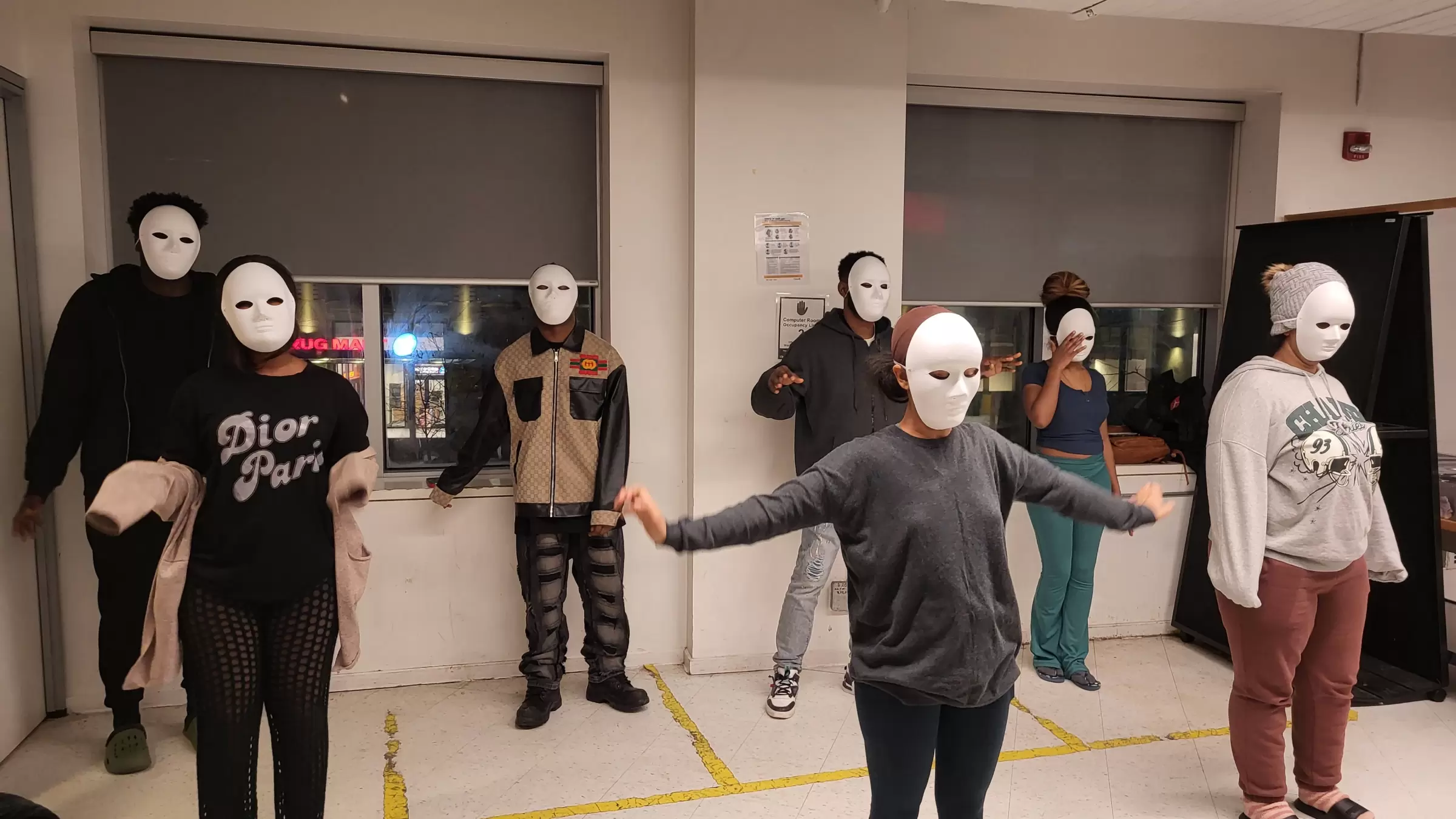

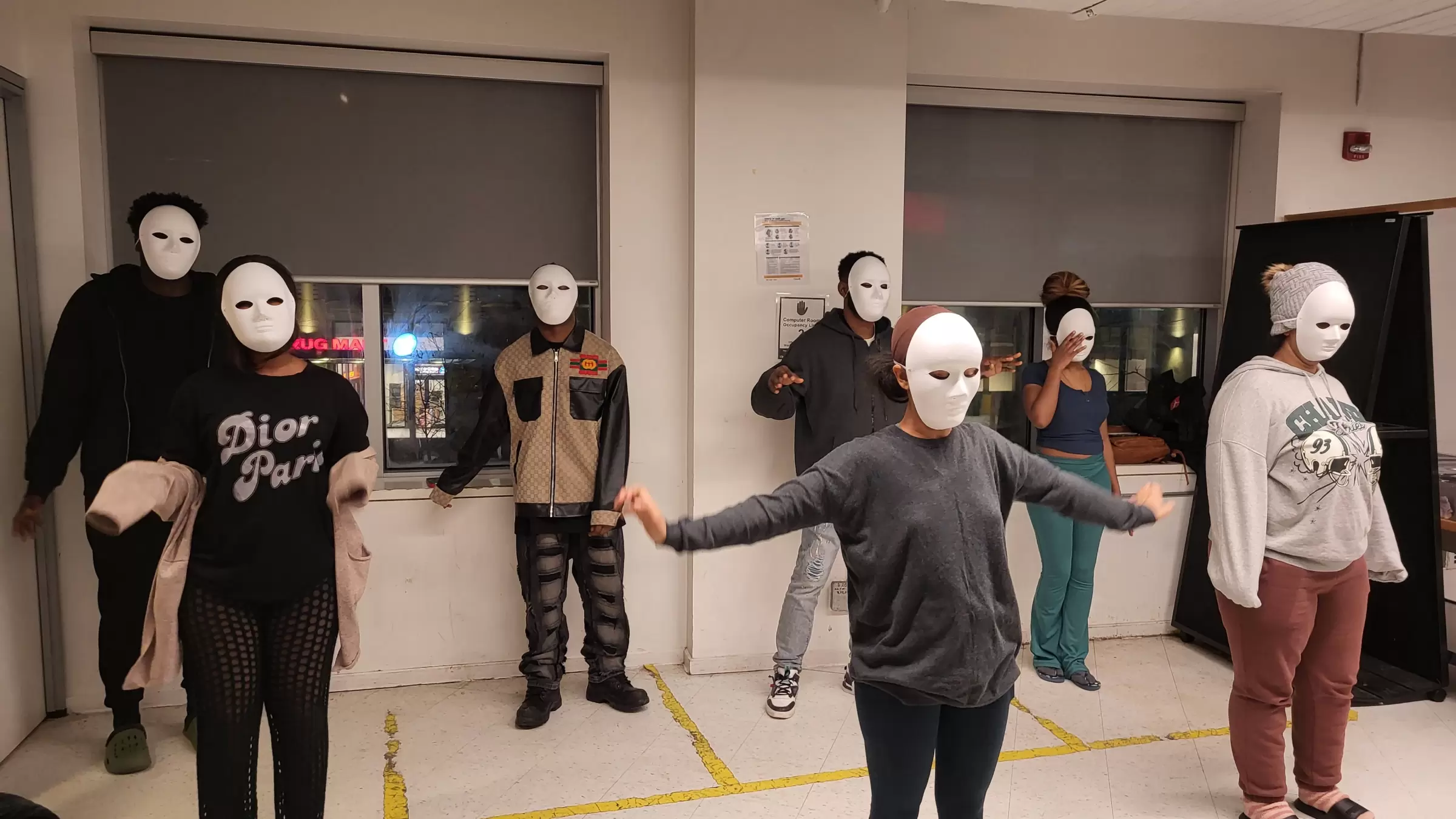

Participants exploring movement and expression during one of Nicolas Bézier’s drama therapy sessions.

Do people come to drama therapy with a specific issue in mind?

Not usually. Most people don’t know what to expect. In a group, you have different people with different lives and challenges. But there’s always a common thread that connects them. Even though it’s group work, I still look at each person individually. I notice small things, and based on the exercises I propose, I might focus on one person more in a certain moment if I feel it will help.

Is it important for people to attend several sessions?

Absolutely. That’s something companies often don’t understand. They see the word “theater” and think it’s a class, or a performance. But art therapy is not entertainment. It’s a therapeutic process. One session won’t do anything. It’s like psychotherapy—you need time. Sometimes it takes four or five sessions for someone to feel safe enough to open up. People need time to explore, to trust, and to understand that there’s no judgment, no right or wrong.

What should people know before starting a drama therapy workshop?

That it’s a safe and cozy space to explore imagination. It’s a chance to discover new parts of yourself and new ways of expressing emotion. But you also need to listen to your boundaries. Don’t go too fast. Take your time and allow the process to unfold.

And for people who want to become drama therapists, what advice would you give?

It’s important to separate yourself from your past experience, especially if you were an artist, a teacher, or a director. For example, I used to run my own theater troupe. I wrote and directed plays. There was always pressure to be ready on time, to sell tickets, to make it perfect. But in art therapy, that mindset is dangerous. You’re not a teacher anymore. You’re not here to direct. You’re here to hold space. You have to let go of control and drop into a different way of working. I’ve seen people in training who still have those old reflexes, like a former teacher still talking to adults as if they’re in kindergarten. It’s important to unlearn that.

So where is the balance between guiding and letting go?

You have to observe more. Body language tells you a lot. The way someone holds their shoulders, the tension in their posture—it speaks. And you have to develop intuition. That’s essential.

Practicing a gentle movement exercise with bamboo sticks during one of Nicolas Bézier’s drama therapy sessions.

How do you build intuition?

In my own life, I meditate, I reflect, and I work on myself. During the training, we had psychology classes and a lot of us did personal therapy as well. I’m also on a spiritual journey—but that’s something I keep separate from the sessions. I don’t talk about spirituality with groups. Some people aren’t ready. But it helps me be more intuitive and present.

What’s one of your most meaningful projects so far?

One of my favorites was a program I did with a French school board in Ontario. I led drama therapy workshops in 16 different schools, focused on preventing addiction in teens. They were 14 to 16 years old. We used improvs and scenarios, like one where your friend wants to use your $50 to buy marijuana, but you’ve saved it for a concert. Or one where your friend is drunk after a party and wants to drive their scooter home. The group has to find a solution. It helped them see these situations from the inside, instead of just hearing a lecture or watching a PowerPoint. They were very engaged, and I saw a lot of maturity in them.

What are you working on next?

A new project based on The Optimistic Challenge—a book by Rossana Bruzzone. It’s a 21-day program of small daily actions: tell a joke, try a new food, do something kind for someone. I’ll run it as a writing and expression workshop for children and seniors together. Every week, they’ll meet to write and reflect on their experiences. It’ll be the first time I run it across generations. I think it’ll be very enriching for everyone!