Breaking, Making, and Starting Again: An Interview with Phil Hansen

A candid conversation with multimedia artist and TED speaker Phil Hansen on destruction as healing, the myth of the “hustle,” navigating creative ruts, and rebuilding an authentic artistic life.

Above: Phil Hansen in his studio, photo by Katie Marek

Phil Hansen has built a career out of turning setbacks into starting points. A multimedia artist, author, and TED speaker, he first caught the world’s attention with his viral art experiments on YouTube, creating portraits out of matches, tattooing bananas (long before Maurizio Cattelan made them a punchline), and eventually destroying his own work in the now-iconic Goodbye Art series. His ideas have reached far beyond the art world: his talks have been viewed by millions, and he has collaborated with everyone from Grammy-winning musicians to global brands.

What makes Hansen compelling is not just the spectacle of his projects, but the honesty behind them. He has spoken openly about struggling with galleries, about the weight of expectation after early viral fame, and about hitting walls where creativity felt like going through the motions. He is now at work on his memoir, Not Famous Artist, which is sure to bring a raw, funny, and unfiltered look at the life of an artist outside the traditional spotlight. As Hansen himself jokes, “a memoir from a living and not famous artist is a tough sell,” but it promises to resonate with anyone who has tried to build a creative life on their own terms.

We caught up with him to talk about destruction as healing, how to stay human in a world that monetizes creativity, and what advice he would give to the next generation of artists.

Your “Goodbye Art” projects turned destruction into a path of emotional healing. What did you discover about art as a tool for processing loss and change? It was an interesting year of destroying art. It all started with a simple question: what would destroying my art do to me and my art. I wasn’t thinking about processing loss and change through destroying art but that was definitely an outcome.

The series made me rethink the value and purpose of art. Like most of us, I was focused on the end product and people’s reactions. Destroying the work forced me to loosen that attachment, and it worked. It also felt like training for future loss. We allprepare for the unknown in different ways. We save money, we rehearse scenarios. I even worked in a funeral home for a while to prepare myself for losing someone close, because I panicked hard when my grandfather died in 5th grade. Goodbye Art gave me some of that resilience.

That said, the first series had a flaw. I found myself lowering the quality of the work, knowing I’d destroy it. So years later, I did a second series where I only destroyed pieces that were “too good to destroy.” It forced me to confront real attachment. And then life tested me anyway: during COVID I had two weeks to move my studio and had to trash half my art and life’s belongings, and a year later, my mom passed away. I do think Goodbye Art prepared me to process those events with more flow and continuity, instead of only pain and grief.

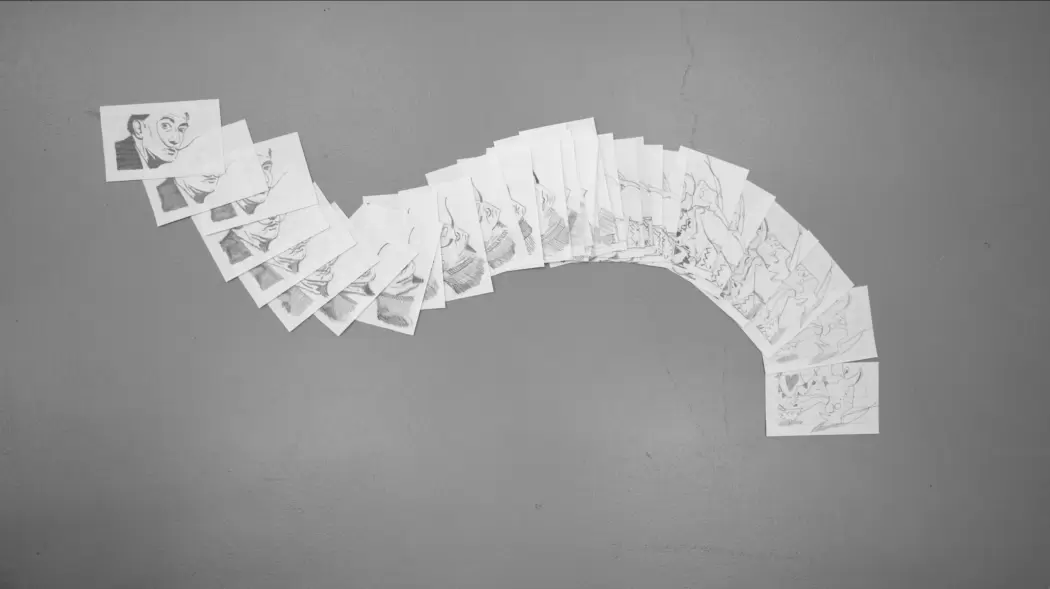

Derivart by Phil Hansen

You became known for viral portraits and video art. Did you ever worry about being boxed in by that identity?

Absolutely. A lot of my early work was portraits of famous people made out of small materials, and the videos of them coming together really took off. That was fun, but I quickly realized I didn’t want that to be my whole identity. People would send me things and say, “This reminded me of you,” and even though I enjoyed those projects, I didn’t want to be defined only by them.

So I pulled back for a while and started experimenting, making pieces just for myself. Sometimes I’d keep them, sometimes I’d throw them away, but the point was to keep exploring until I could say, “This is where I want to be.” Because when you try to turn your passion into a living, you end up following attention to some degree. That’s very different from digging into something deeply personal, where you don’t care what others think and just want to figure it out for yourself. Some of those side projects were weird and unlike anything I’d normally make, but that was the point: to push myself into new territory.

If you strip away career, money, or recognition, what role does making art play for you purely on a personal, human level?

At first I wanted my art to bring those things, but over time I realized I just wanted to make things, not always share them. For the past few years I’ve kept most of my projects to myself. Not because I’m overly private but because sharing work with people can change the perception of it. Most of my projects are about scratching that “unknown” itch. Like going off trail on a hike, throwing weird spices into a recipe, or customizing a sweatshirt so it says PANTS in bold letters across the front. A lot of my work starts with a question: Could I work with fingerprints like Chuck Close did but put my own twist on it, can I handwrite stories people have shared with me to make a picture, or could I use the decaying process to draw on a banana? It turns out, for the banana question, I could with a push pin to scar the skin which would darken and allow a drawing to take shape. And when I first did it, Google Images had zero banana-decay artworks. Now there are tons. Ha.

So for me, art is about pushing into the unknown, being uncomfortable, failing, and finding a way out. That’s the human part.

In your book you describe feeling like a “Tinman, all clanky motions with no heart” when creativity stalled. How have you learned to accept those stuck moments as part of the process?

“The process” has so many goals, emotions, and expectations tied up in it beyond just making the work. Feeling stuck can be less about technique and more about untangling what’s in my head. It’s a real “lay on the couch and talk it out” kind of thing, almost like therapy where the art is both the patient and cure.

So, yes I have accepted feeling stuck as a necessary part of the process because it happens all the time, so I might as well accept it rather than lament it. Also I have a little venn diagram that I’ve made that really helps me. It feels silly but this has kept me moving forward on projects as much as drinking water and taking a nap can help my mood. If one of these components is missing, I’m stuck. For me, it’s usually motivation. The diagram gives me a way to ask and answer “what’s missing” instead of just distracting myself with cleaning the studio or a glass of wine.

You’ve interviewed other artists about how they get unstuck. Did you notice any common threads in how creative people navigate those ruts?

Here’s the blunt conclusion most artists don’t love but usually admit is true.

- They’re judging their ideas too harshly.

- They’re just not into the work anymore.

As kids, we sketch freely but maybe a classmate says we suck at drawing, we get a bad grade in art class, a parent says “you should put your energy into something useful” and in art school a critique feels more personal than useful. All of those things become layers in a filter that slow down our willingness to bring an idea to life. Often without us noticing. By slowly allowing ourselves to create more freely over time we can reduce the size of ruts we encounter.

On the second point is a little tricky and nuanced. Early on, school forces us to make art so we don’t get the chance to really know if we really like what we are doing. Many people get out of school and instantly stop creating. Or they go back to school to get a masters and think that will light the fire under them. Like, if you sign up for a 5k and do some prep. The day comes and you do the run. How many people are going to keep running and do a 7k? Finding intrinsic motivation is tough for many people. But let’s say someone has that motivation and has been making art for many years, even decades. A lot of artists are exploring a question, a material, or theory. It makes sense that after working on it for many years an artist may have explored what they intrinsically want to explore. If that desire has faded, then it’s up to us to find other motivations. Or, and there’s nothing wrong with this, move on to explore other things. I’ve always thought of myself as someone who likes to make things, most of the time it’s art, but other times it’s a piece of furniture, or working on a book.

What I’d really like for people to see is they are probably not “in a rut”, they are probably not “stuck”, but instead they have naturally found themselves in a place of not creating as much. So go look at your own venn diagram of Creative Production and think about learning a new skill, working on an idea you didn’t think was worth your time, and find what excites you to get creating again and GO!

Phil Hansen working on primary Blue

What’s the biggest myth about the artist’s life that you think fuels feelings of failure or depression when reality doesn’t match up?

Can I give you two? The biggest myth right now is that if you’re good at something or enjoy something, you should turn it into a hustle. That pressure to monetize passion is crushing. The art you once made for joy becomes art you make for likes and money which is a completely different goal and that’s the fast lane to feeling like a failure.

The other myth is moving fast. Our daily world moves at a wild pace that we often don’t recognize. Then someone comments that a news headline we’ve forgotten about was just 4 months ago not 2 years ago. This speed makes us think the gallery world operates the same way. NOT AT ALL! With art and galleries we need to shift our sense of time drastically. If we think things will happen in weeks or months that can lead us to think we failed. It’s like trying to lose weight. If we weigh ourselves daily and freak out that nothing has happened vs weighing weekly with a reasonable goal in mind our perception of the results is completely different. So look at the time scale most artists work in for shows and expect roughly that. It might be hard to imagine your first show is two years away when you feel ready now but time marches on and two years will eventually show up.

Do you think the rise of digital platforms has made the art world more democratic, or just shifted the gatekeepers?

Digital platforms have definitely made things more reachable and democratic. There are still gatekeepers of certain realms but the middle price point has opened up in a big way.

It used to be that coffee shops, small galleries, and art fairs were the place most artists got their start. Now, anyone can make their work available in numerous different ways online. This means it’s easier than ever for an artist to make money from their work. But the higher priced works are still much more likely to go through galleries.

You’ve had encounters where galleries told you you were both “too big” and “too small.” What do you think that reveals about the gallery system?

When I was told that it was around 2007 and the old gallery model was in place. Pre social media galleries focused on their collectors within their local. I was applying for shows and my resume listed millions of video plays, and numerous interviews on CNN, which sounds great but at the time it felt like I was showing off my shiny rocks; galleries just didn’t know what to do with it. Social media was just beginning to restructure our lives, galleries included.

What I think it says about the gallery system is there has been vast change in the last 20 years that isn’t immediately obvious because it’s been a slow morphing blob. These days in addition to the traditional galleries there are some that specifically look for artists with followings knowing that they can reach the same small number of collectors globally as a gallery would have previously done locally. We also have a lot more galleries that don’t have a permanent space. There’s a lot more flexibility out there which is great.

You even turned your own studio into a gallery. What did that experience teach you about what artists can do differently from the inside?

Oh my word, too much to say, and I’ll leave out the half-baked stuff. Can I give you a twofer again? Ha. Apparently this is my MO.

My first tip for artists aiming at galleries is to Analyze and Approach. Take time to study the galleries in your area. Ask what their goal is: are they focused on decorative work or on representational stewardship? What do they do for the artists they work with? Does your work fit their program? How do they seem to find new artists? After analyzing, yes even making a spreadsheet, decide which ones you genuinely want to approach. Many artists are just so damn excited for a chance to show their work that they apply to a bad fit and end up discouraged by rejection. I say that from personal experience. Here in Minneapolis there are dozens of galleries, but only four that meet my criteria for showing, and only one where my work somewhat fits. That means I need to apply in other cities. Nothing wrong with local galleries, nothing wrong with me. It is simply how things are.

The second tip comes from asking yourself, “Do you really want to be in a gallery?” Many artists are told to aim for gallery representation without much thought as to why. For many, it’s an outdated model of the art life. Today, artists often prefer the flexibility of art fairs, self-organized or group pop-ups, or platforms like Patreon. In my experience, most artists want more flexibility than a gallery allows.

It’s a beautiful mash of things that we refer to as the Art World. School doesn’t break it down in a meaningful way which is a bummer. It’s up to us to sort it all out and find our path!

Looking back, what advice would you give to an emerging artist?

Oh wow, this sounds like the last question. Um.. I’ve said a lot.. but I think the two biggest things artists need to do is maintain reproductive control in their lives and always be saving money.